An ice tongue occurs when a glacier projects rapidly out into an ocean or a lake, usually in the form of a floating platform. The title of Ohan Breiding’s exhibition and video, Belly of a Glacier, fills out the metaphor, asking us to consider the manifold poetry of ice: as body, animal, witness, record—our “oldest archive.”

This is not a merely tropological proposition. The setting and subject of this work is the US National Ice Core facility, in Lakewood, Colorado, which is the largest archive of ancient ice on the planet. Within this unremarkable-looking warehouse building is a freezer that is kept at -36 degrees Fahrenheit year-round, within which are steel shelves of aluminum tubes that house cylinders of ice, some of which can be traced back hundreds of thousands of years. The repository’s workers, who are called “curators,” receive, archive, and take care of the ice, which must be painstakingly protected. Glaciologists, hydrologists, and historians alike rely on these archives, not only because within ancient ice is the history and science of so much of what we think we know about climate change, but because the ice contains many other histories as well: of famine, war, democracy, even art, the traces of which, both real and imagined, are the subject of this exhibition.

The center of the exhibition is Belly of a Glacier, a nine-minute single-channel video written and directed by Breiding, with a contrapuntal score by Jules Gimbrone and cello performed by Taz Kim. The opening scene is of an ice-core drilling in Greenland, the shot hinging on a large wagging flashlight that illuminates the excavation’s exit from the ice. As we enter the ice core facility, yellow text on the screen poeticizes what we are looking at: “Styrofoam sarcophagi … receptacle for ice” and “machinery keeps it alive, routines of constant care.” The film’s low angles and tracking shots, text-narration of how the body reacts to these conditions (“blood vessels constrict, the skin on the neck gets thin”), all against a fluctuating suite of dissonant cello sounds, is reminiscent of the horror genre. The suggestion is foreboding: though the function of this practice may seem esoteric, in trying to keep this ice alive, the ice curators are under tremendous atmospheric and societal pressure: to prevent us all from a terrifying future.

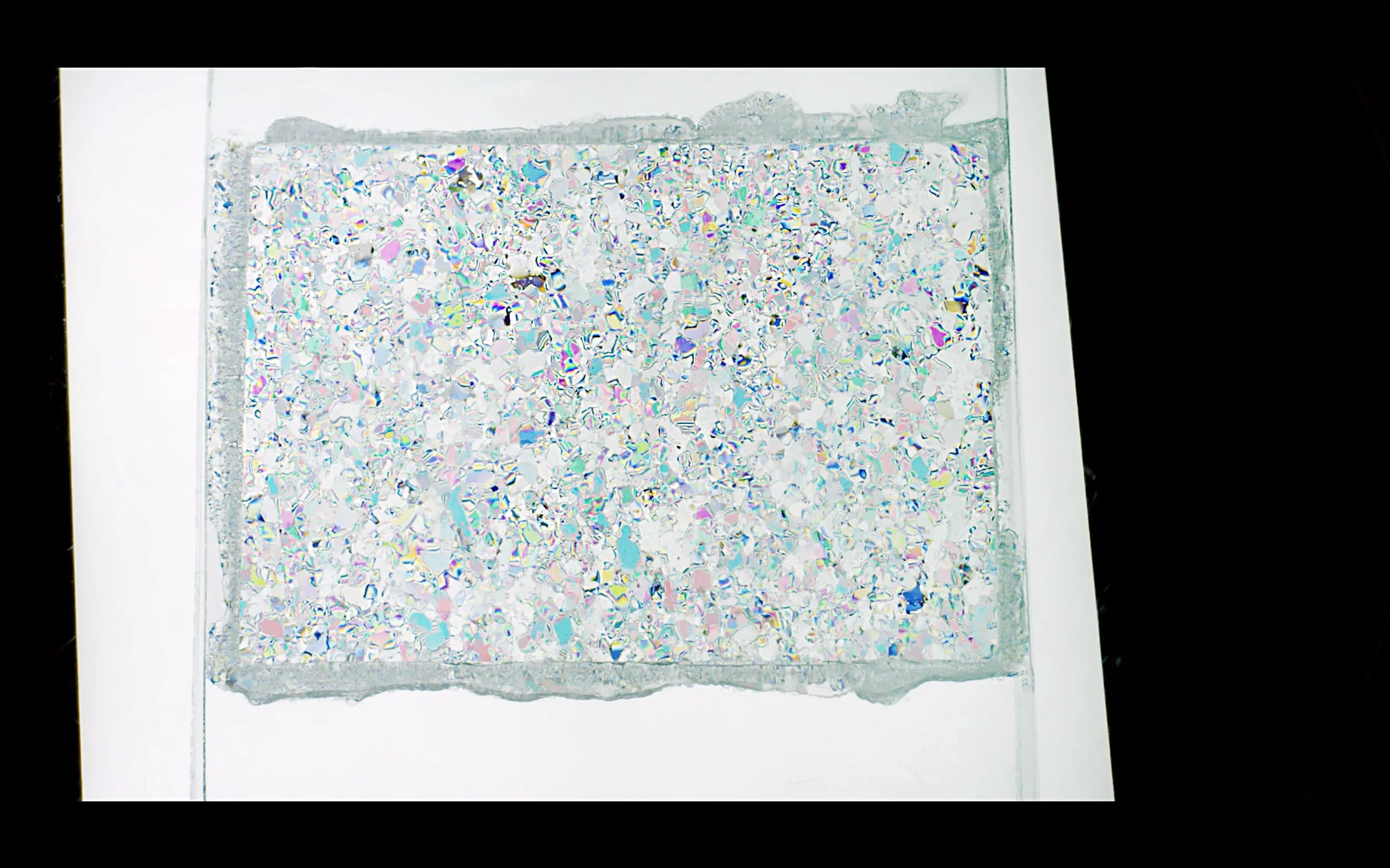

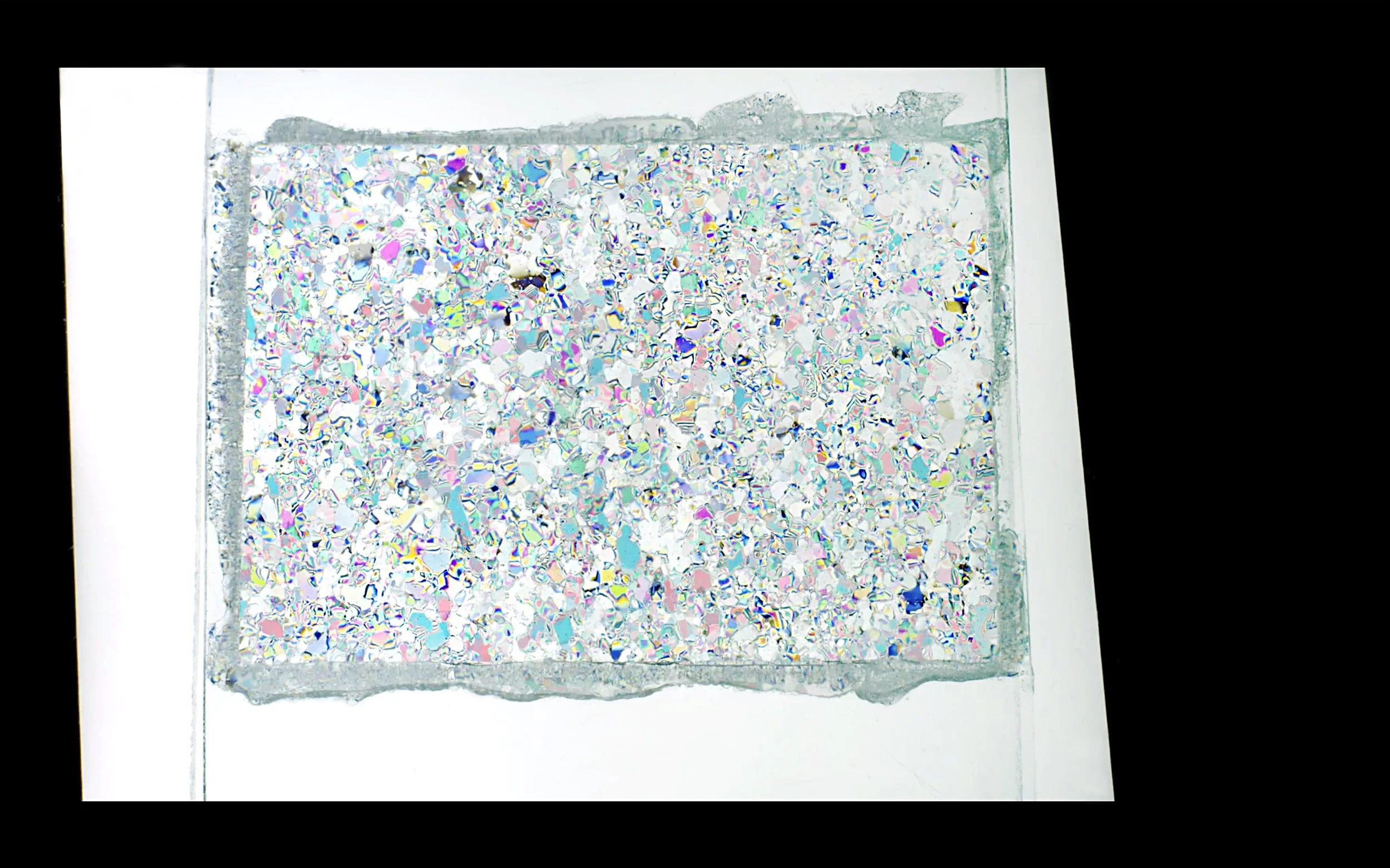

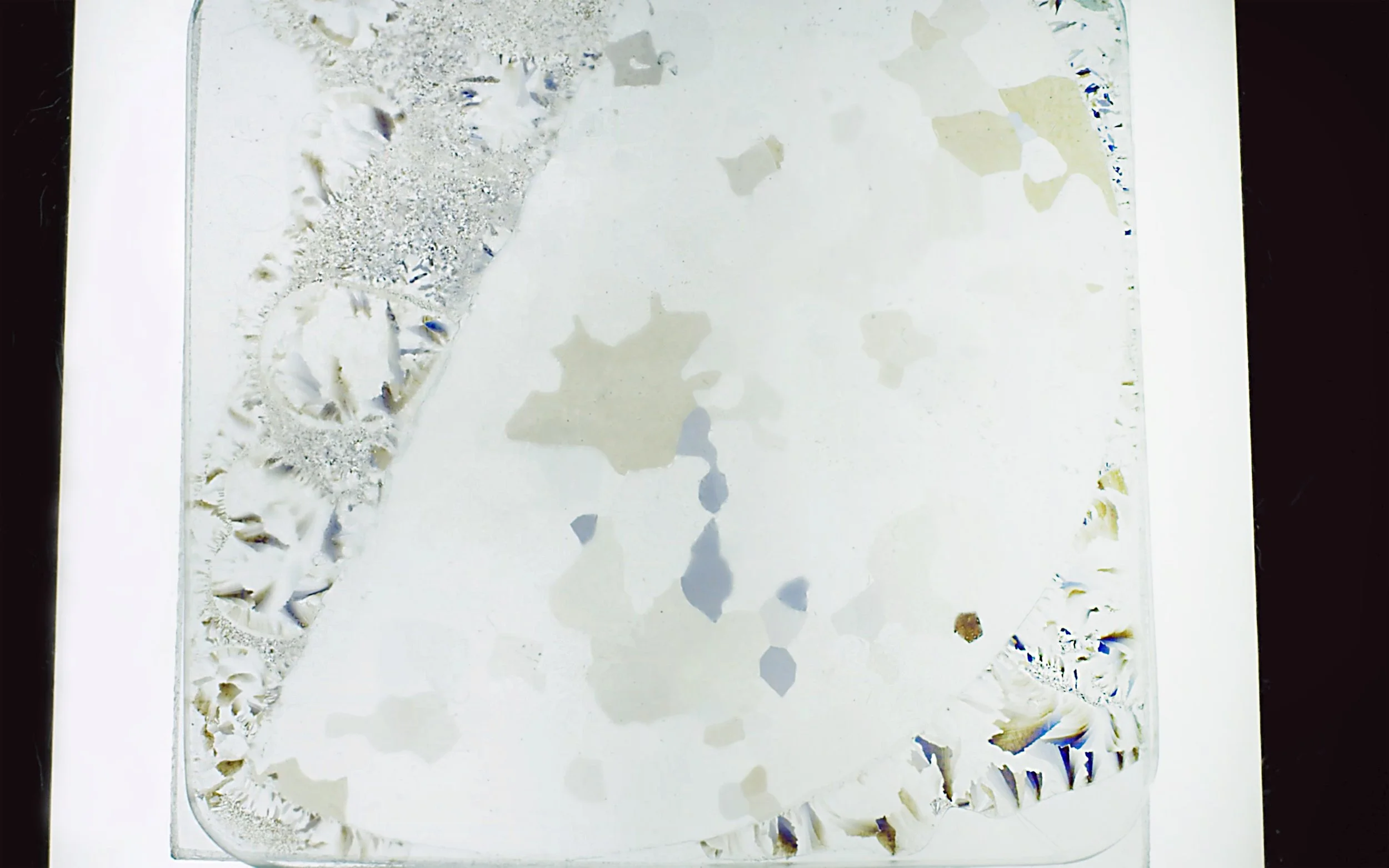

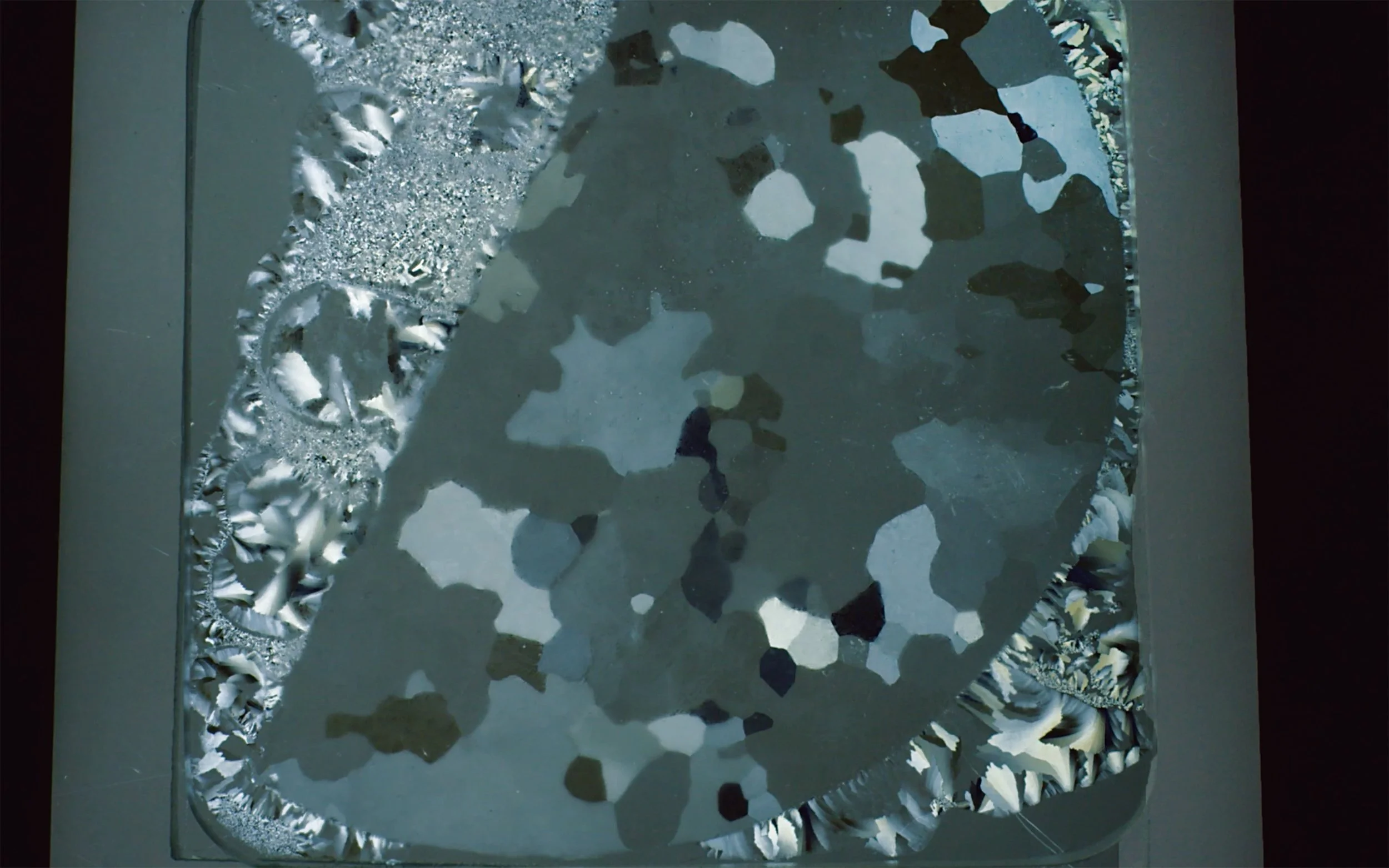

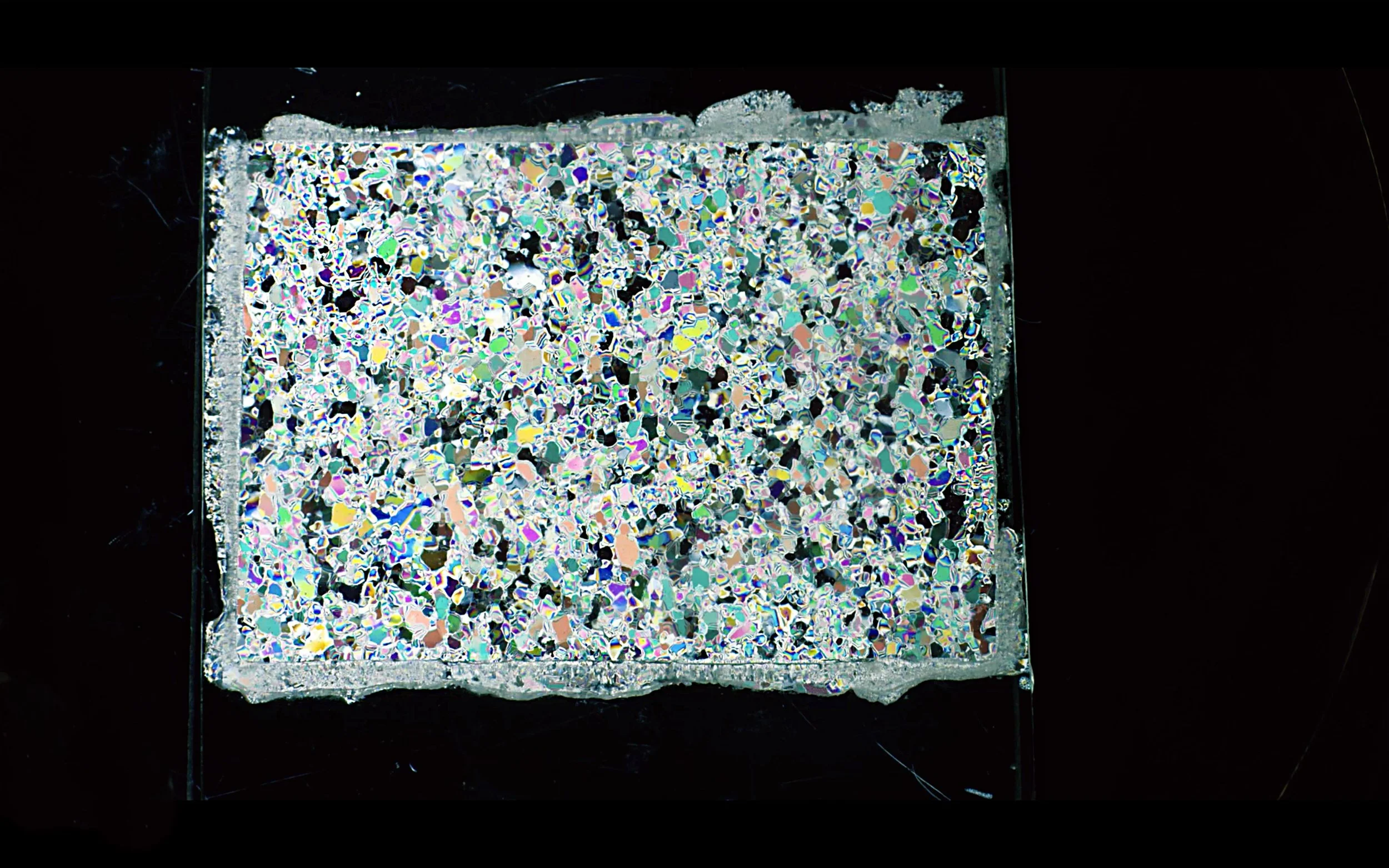

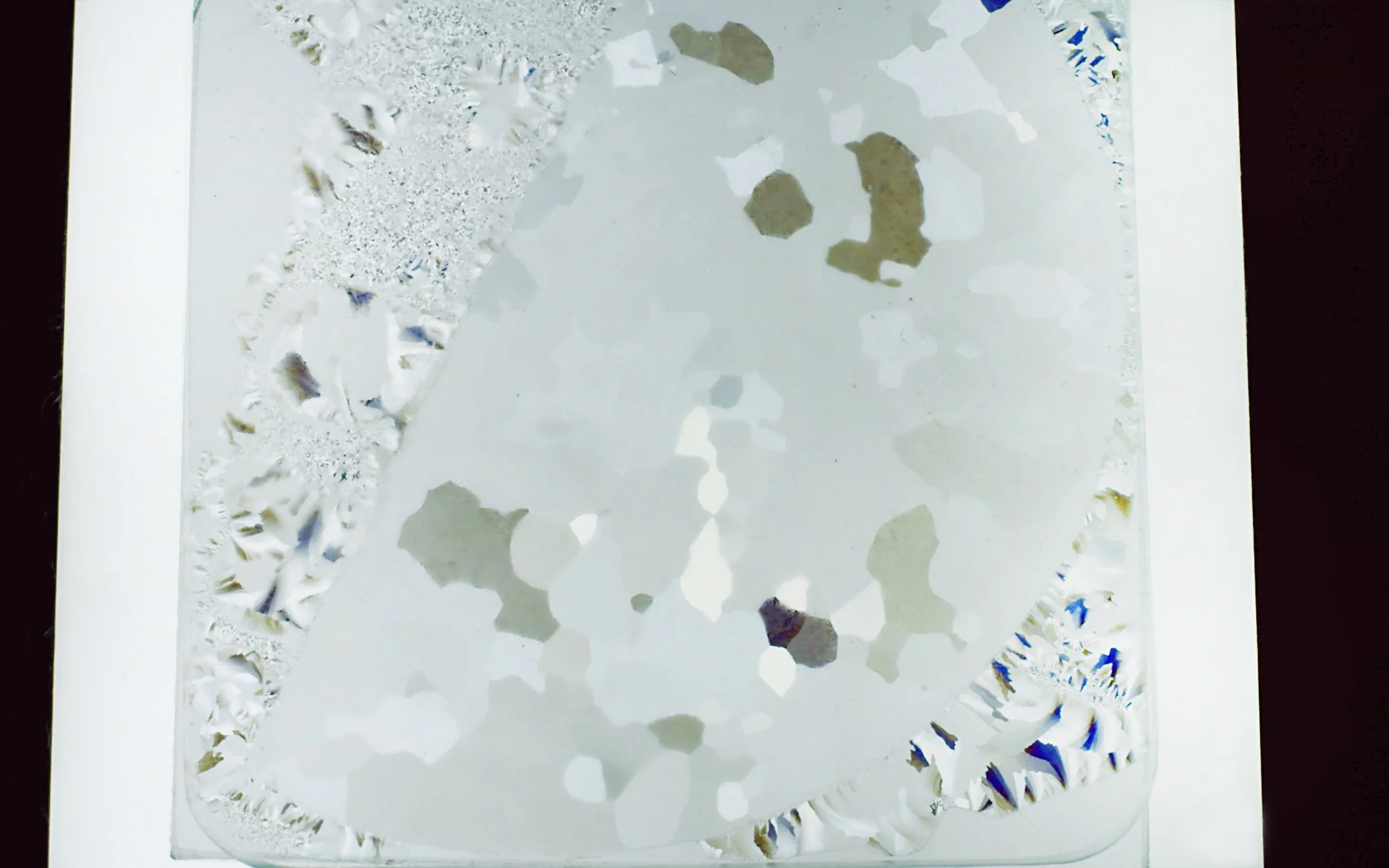

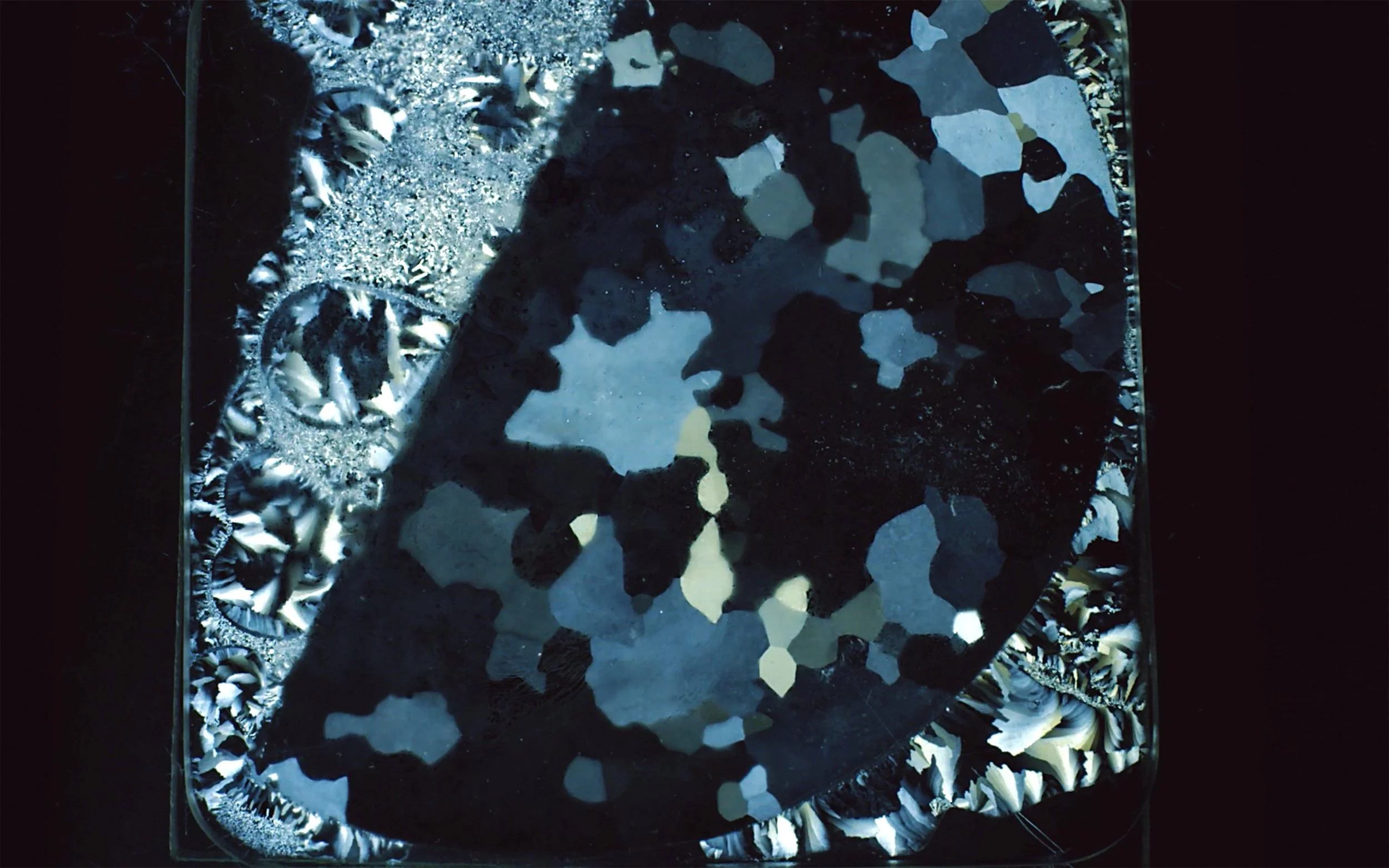

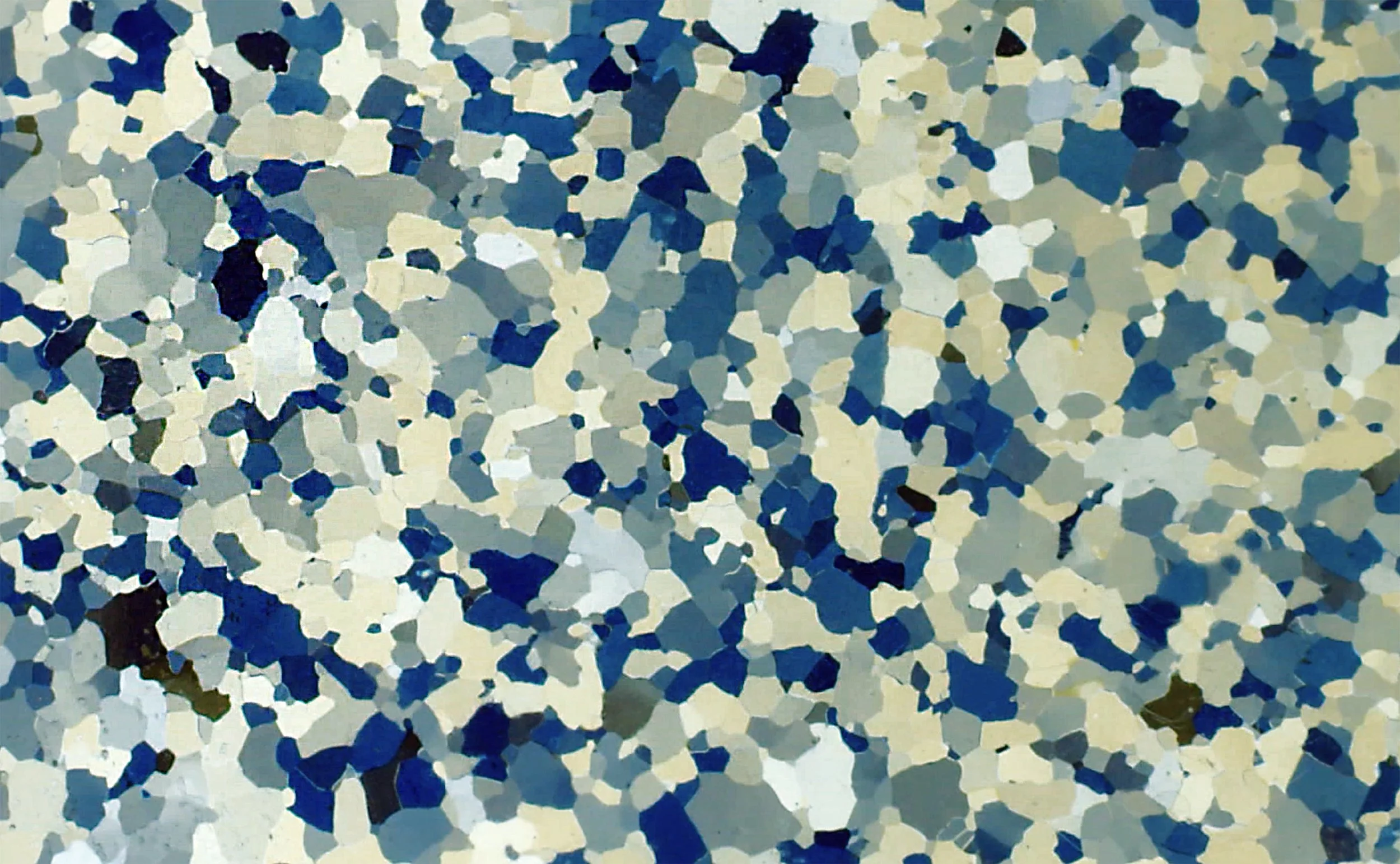

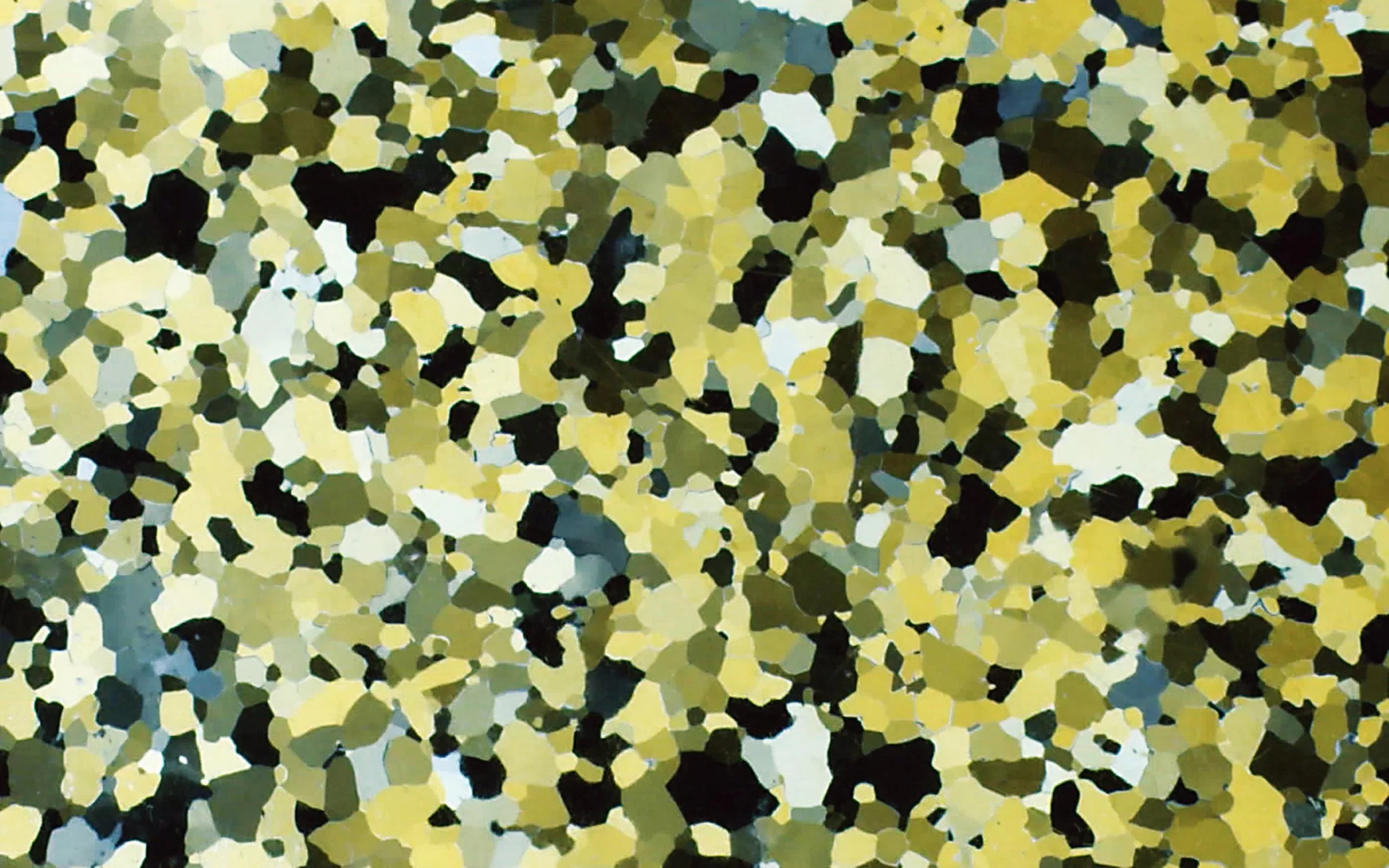

The closing scenes of the video show images of ice crystals viewed through the polarized lens of a petrographic microscope: “Ancient atmospheres are trapped in air bubbles, a matrix of crystals,” reads the accompanying text. The colors and shapes shift according to the light and depth at which the ice slivers were cored, creating a kaleidoscopic, colorful effect that evokes stained glass, shimmering mosaics, camouflage. The images are also extrapolated onto the walls of the exhibition in the form of twelve digital c-prints, intimate portals into the ice for the viewer.

Breiding, whose work in photography, video, and installation, often plays with the theme of “landscape as witness” and is interested in how environmental events can lead to political upheavals. They found their way to the ice archive through the study of the eruption of Alaska’s Mount Okmok in 43 BCE, which led to a ten-year global coldsnap, causing famine, the freezing of crops, and, ultimately, the fall of the Roman Republic. The final element in the exhibition, a photograph of a drywall sculpture, is a lyrical coda, a lexicon of stories, that the ice is specially equipped to tell. Into the white drywall, which denotes a snowy landscape, is lodged an array of objects: golden spikes collected on the artist’s walks across the railroad tracks to their studio, coins and other metal objects dating back to Ancient Rome, a photograph of Vesuvius erupting, a piece of a meteorite, the Pegasus Mobil oil logo, bird feathers, a pipe, volcanic ash, a Mercedes Benz hood ornament, beeswax prayer candles. The collection of symbols visualizes toxic matter, which is contained in the atmosphere and often invisible, creating an index of past-present-future remains.

—Svetlana Kitto

Belly of a Glacier, still from video

HD video, sound

9 Minutes

2023

Edition of 2 + 1 AP

Diamond dust I-IV: 68000-year-old atmosphere trapped in West Antarctic ice

Giclée print on Elegance velvet fine art paper, 14.4”x 9”

2023

Edition of 5 + 2 APs

Diamond dust I-IV: 68000-year-old atmosphere trapped in West Antarctic ice

Giclée print on Elegance velvet fine art paper, 14.4”x 9”

2023

Edition of 5 + 2 APs

Diamond dust I-IV: 68000-year-old atmosphere trapped in West Antarctic ice

Giclée print on Elegance velvet fine art paper, 14.4”x 9”

2023

Edition of 5 + 2 APs

Diamond dust V-VIII: 123000-year-old atmosphere trapped in Greenland ice

Giclée print on Elegance velvet fine art paper , 14.4”x 9”

2023

Edition of 5 + 2 APs

Diamond dust V-VIII: 123000-year-old atmosphere trapped in Greenland ice

Giclée print on Elegance velvet fine art paper , 14.4”x 9”

2023

Edition of 5 + 2 APs

Diamond dust IX-XII: 54000-year-old atmosphere trapped South Pole ice

Giclée print on Elegance velvet fine art paper, 14.4”x 9”

2023

Edition of 5 + 2 APs

Diamond dust IX-XII: 54000-year-old atmosphere trapped South Pole ice

Giclée print on Elegance velvet fine art paper, 14.4”x 9”

2023

Edition of 5 + 2 APs

Diamond dust I-IV: 68000-year-old atmosphere trapped in West Antarctic ice

Giclée print on Elegance velvet fine art paper, 14.4”x 9”

2023

Edition of 5 + 2 APs

Diamond dust V-VIII: 123000-year-old atmosphere trapped in Greenland ice

Giclée print on Elegance velvet fine art paper , 14.4”x 9”

2023

Edition of 5 + 2 APs

Diamond dust V-VIII: 123000-year-old atmosphere trapped in Greenland ice

Giclée print on Elegance velvet fine art paper , 14.4”x 9”

2023

Edition of 5 + 2 APs

Diamond dust IX-XII: 54000-year-old atmosphere trapped South Pole ice

Giclée print on Elegance velvet fine art paper, 14.4”x 9”

2023

Edition of 5 + 2 APs

Diamond dust IX-XII: 54000-year-old atmosphere trapped South Pole ice

Giclée print on Elegance velvet fine art paper, 14.4”x 9”

2023

Edition of 5 + 2 APs

Note: All Diamond Dust photographs are framed with thin black painted wooden frame and museum glass

“We write our names in the sand and then the waves roll in and wash them away,” Augustus (First Roman Empire 27 BC until his death in AD 14)

Light antique plaster, 16.5”x 9.5”x 10.5”

2023

Edition of 1

Atmosphere Codex: Ancient Roman coins, golden spikes, tobacco pipe, stained glass church window fragments,

Mercedes Benz hood emblem, volcanic ash, photograph of Vesuvius erupting, Pegasus Mobile oil logo, beeswax candles, meteorite

Giclée print on Hahnemühle paper, 31”x 37.6”

2023

Edition of 5 + 2 APs

Gallery heating system set to a lower temperature throughout the run of the exhibition